The height of the console wars between Sony, Nintendo and Sega was undoubtedly a trial by fire for developer and publisher alike. These companies had invested huge sums towards the promotion of their respective platforms, and studios hired the most creative minds to develop that one game that would elevate them above their competitors. It is here that Sega turned to Yu Suzuki.

Now while gamers enjoyed an idyllic time in which studios created brilliant games to gain market dominance, one fact had become clear: Sega was falling behind. Nintendo had the mascots and Sony had massive 3rd party support, but Sega was stuck with a library for their Dreamcast console that just couldn’t gain a foothold. Sonic and the gang simply failed to bring in sales from this competitive market.

Fortunately Yu Suzuki had been developing an idea since the previous generation for not just a new IP, but a kind of game that didn’t even have a genre yet. Yu Suzuki had long been at the front line of the console wars, but the game he was about to pitch for the Dreamcast had grand ambitions worthy of Sega dropping an initial budget of a whopping $47 million. This game was Shenmue.

Sega’s killer app

Whereas Shenmue is more typically remembered for introducing modern, quick time events to the gaming world, which indeed it did, its true legacy lies in how Yu Suzuki had conceived the world’s first, 3D, open-world game. His team at Sega AM2 used their astounding pile of cash to invest not in action or explosive set pieces, but in pushing the boundaries of the player’s immersion.

When their masterwork finally released in 1999, gamers found themselves entering more than just a digital playground for the protagonist, Ryo Hazuki. The town of Yokosuka was a fully-realized mini-universe filled with distinct characters, various side activities, and a day-night cycle which was woven into the core of a beat-‘em-up, kung fu adventure. Truly a feat for the 90’s.

In short, Shenmue’s world and its revolutionary graphics felt like a reality not just to play in, but to live in. Yu Suzuki had a vision of making players a part of his game by giving them the freedom to progress at their own pace. Shenmue had instantly created a paradigm for how a new generation of games should personify the open-world genre, and its legacy is clear in everything from Grand Theft Auto to Assassin’s Creed.

The neverending story

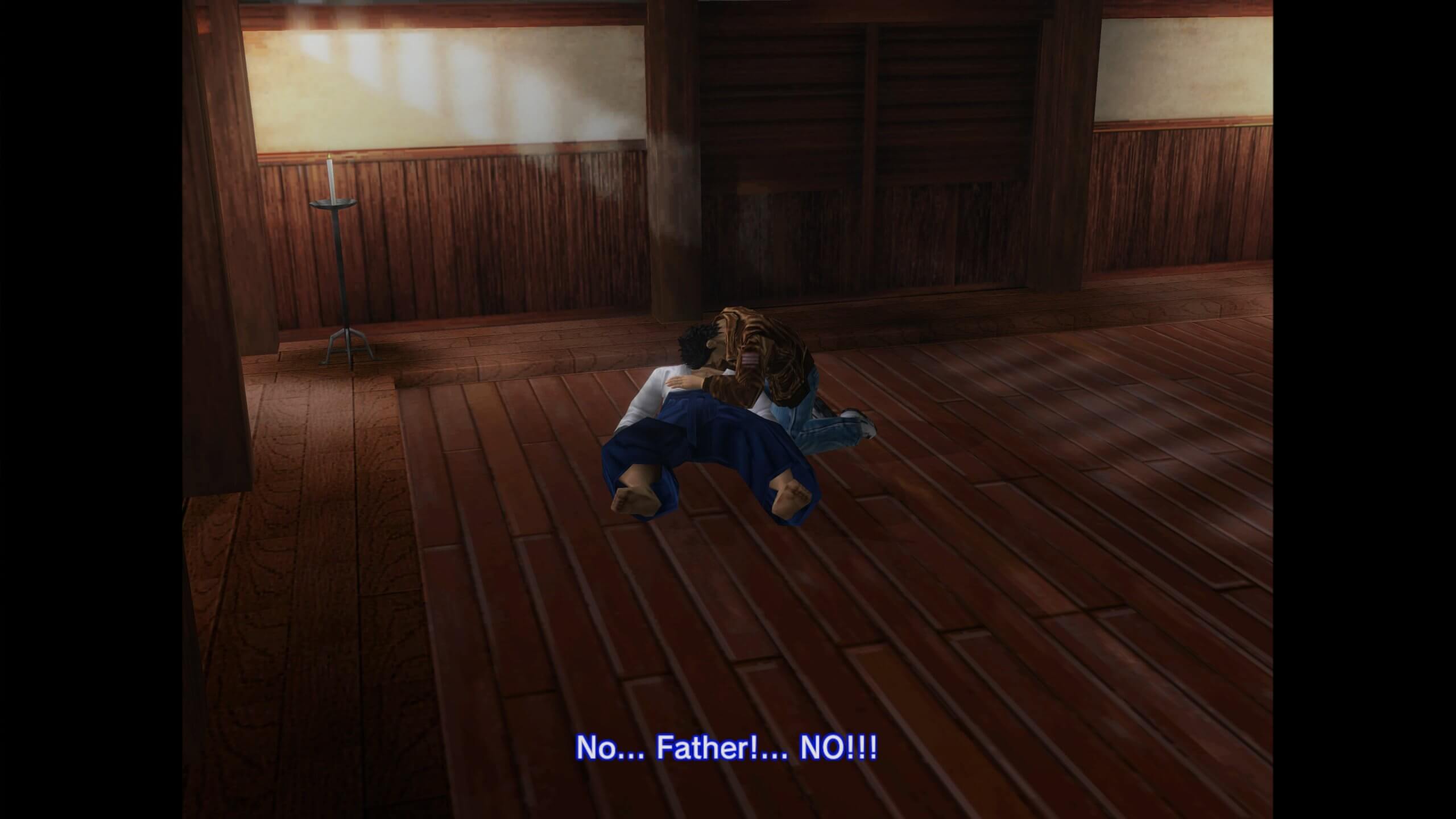

In terms of the actual narrative, Shenmue shared many characteristics with those 80’s Jackie Chan movies I used to watch as a kid on Friday nights. You play as Ryo Hazuki, a budding martial artist who witnesses his father being murdered over an ancient artifact named the Dragon Mirror.

The murderer in question is the formidable kung fu master, Lan Di, who journeyed to Japan once he learnt of the artifact’s hiding place in the dojo under the tutelage of Ryo’s dad. After forcing Ryo’s father to hand over the mirror with his dying breath, Lan Di returns to China with his prize, leaving the flames of vengeance burning in Ryo’s heart.

The stage is set, and Ryo pursues his father’s killer starting with only scraps of information he can salvage from the villagers of Yokosuka. He eventually picks up the trail of breadcrumbs, but in so doing encounters some nasty people willing to defend the secret of Lan Di’s whereabouts with their lives. So, like Jackie, Ryo uses kung fu to bash some answers out of them, and thus improves his own fighting techniques along the way.

Sadly, our hero appears to be broke, which is where the infamous forklifting gameplay came in. Shenmue also used its immersive open-world as something of a pragmatic diversion where Ryo could earn some moola by doing mundane chores, such as forklifting for cash. Yet all work and no play makes Shenmue a dull game, which is why Yu Suzuki filled his world with real side-activities also, such as going to actual arcades in the town.

Enter Shenmue III

The substantial following garnered by Shenmue and its sequel is testimony to how innovative the experience was. Yu Suzuki could not save the Sega Dreamcast, but droves of gamers loved this newfound freedom of exploring unrestrained through both games, helping Ryo with his detective work, practicing kung fu moves, or just trying their hand at all the mini-games. People wanted more.

So why the drawn-out pre-amble you may ask? Well, Shenmue III is one of those games that you will probably only like if you really understand where its coming from. Shenmue III is such raw, undiluted fan service, so devoted to its source material and legacy, that it seems utterly inseparable from the bigger picture.

Seriously, I played both the remastered ports last year to see what the fuss was about, and rather than feeling like a separate game, my time with Shenmue III often felt like playing an re-textured expansion mod. On the one hand, this works in the game’s favour since this is a true sequel in Shenmue’s eleven-part saga. On the other, certain aspects of this game are desperately in need of some modernisation.

Why it works

As if nearly two decades haven’t passed, Shenmue III takes off right where players were left hanging with the previous game. Ryo has since made it to China in his search for Lan Di and finds himself in Bailu Village, a remote little hamlet nestled in the mountains known for its culture of martial arts and stone masonry. It is also here where both the Dragon Mirror and its companion, the Phoenix Mirror, were created.

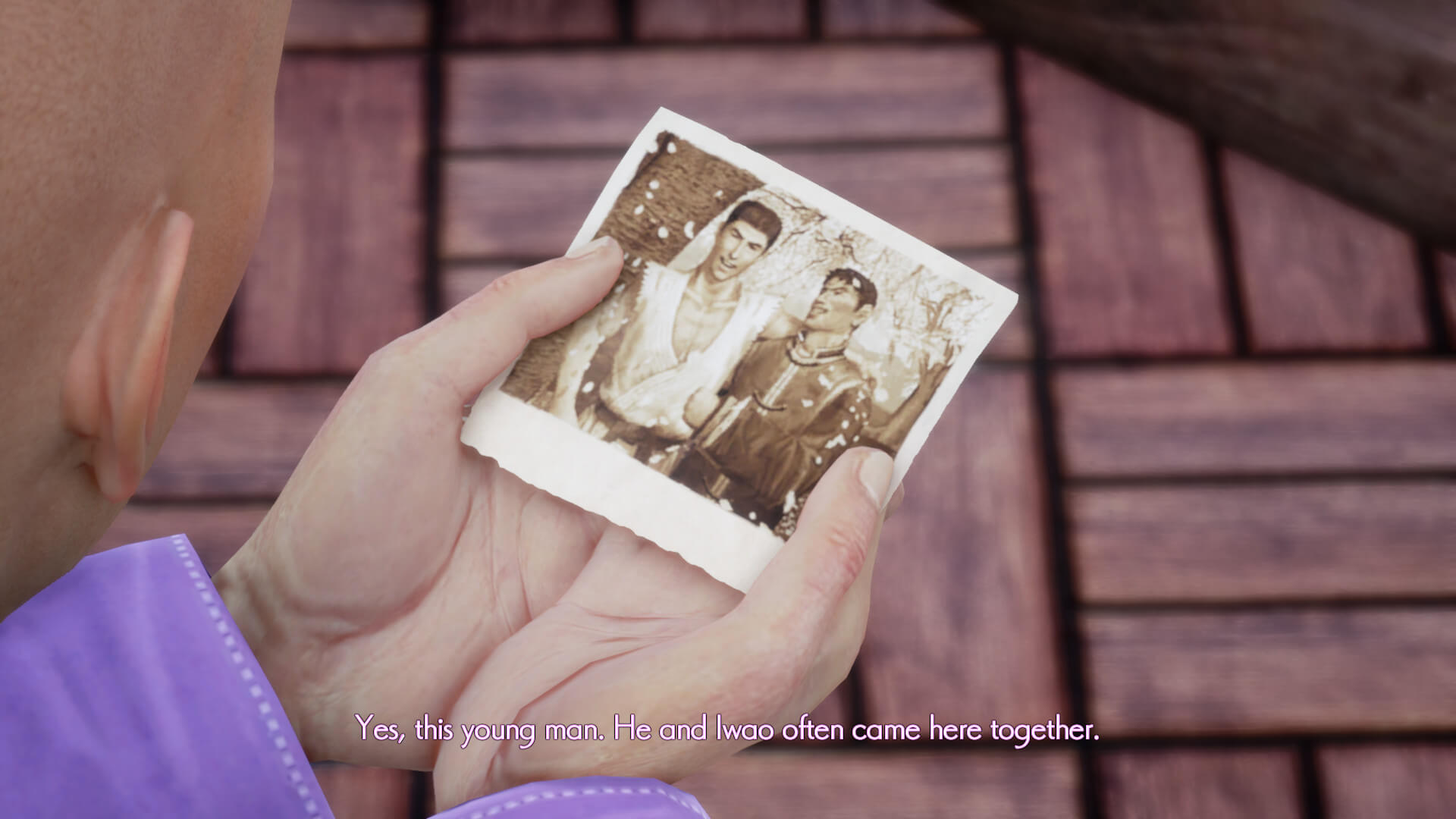

Ryo has also befriended Shenhua, the daughter of a kidnapped stonemason involved with the mirrors’ creation, and in the words of the often repeated loading screen, “their fates becomes entwined”. As is the modus operandi from both prequels, the gameplay is once again centered around searching the village one small clue after another, taking Ryo ever closer to Lan Di.

Every time I launched Shenmue III (or the prequels) I inhaled, exhaled, and just relaxed as I luxuriated in the bliss with the game gently unfolding before me. It is like Tai Chi transformed into a game.

Bailu Village is one of two main hub worlds that opens the game opens, and it is an absolute Shangri-la of green mountain fields, majestic peach trees in blossom, and villagers just going about life serenely. While lacking the the more complex textures of a AAA title, the Unreal Engine 4 does the job beautifully here, and it it augments the game’s tranquility and total lack of stress.

As Ryo continues his search of Lan Di’s whereabouts, and learns more of how this village leads to his father’s murder, the player is never rushed, or urged to progress. If you get tired of talking to people or beating up the thugs harassing the villagers, go fight some of the monks at the local dojo, help the old shopkeeper chop some wood, try your luck at the various ‘pop-up casinos’ to buy Ryo some new threads, or… drive a forklift hahahaha.

Like I said, this is a thoroughbred entry in the Shenmue franchise and these fun (if perhaps somewhat meaningless) mini-games create the illusion that the player has left the real world behind. You get to embody Ryo not in over-the-top action scenarios, but in a variety of smaller, more routine situations that we ourselves could actually relate to and thus bringing the player closer to his character.

There have been other minor tweaks to the formula as well. Aside from the obvious graphical upgrade, Shenmue III sometimes lets the player skip ahead to an objective’s location and time, eliminating the need to wait. The fighting also feels more responsive and easier to master since Ryo now executes moves automatically once the player becomes skilled in executing a particular technique.

Why it doesn’t work

For all the occasional forklift driving, quick time events, casual character interaction, kung fu and other staples of the Shenmue franchise on display, the very character of the third installment also represents its biggest weakness. While Shenmue III smashed Kickstarter records, and while a dedicated fan base still upholds their beloved franchise, this game belongs mostly to them.

I get that Shenmue was originally conceived as a sixteen-part epic (which was later cut to an eleven-part story covering four or five games), but the narrative just does not feel like it moves much further from square one. Ryo hardly makes any progress towards avenging his father, and the overall plot is beginning to show signs of fatigue. I think Suzuki needs to consider wrapping things up.

The relaxed and tangential gameplay is also likely to ring hollow with players wanting to see their grinding translate into something more substantial (as with, say, more modern RPG’s). It is true that the martial arts training is useful to a certain extent, but I frequently found myself doing something in the game only to wonder what on earth the point of this activity was.

Again, it must be remembered that Shenmue III is attempting to make a seamless transition with the first two games which took shape in a climate that had never seen any of this before. Bringing this forwards to the current generation creates a charming sense of continuity, but this does make Shenmue III a noticeably asynchronous experience when placed next to modern games it inspired.

I don’t really have an issue with the graphics given that this game’s budget places it on the lower, middle shelf. In fact, it even puts other releases with five times its budget to shame in certain moments. Still, many players would likely be put off by the rather robotic look of the NPC’s regardless. Where I see old-school charm, others are guaranteed to perceive the visuals as lacking and dated.

One for the fans

Despite the community thinking Yu Suzuki’s most passionate project had died with the very console it was trying to preserve, here we are, eighteen years later, thanks to the magic of crowdfunding. Instead of trying to establish itself as a new JRPG force to be reckoned with, Shenmue III seeks to pay tribute to what players loved and remembered about Suzuki’s answer to Sega’s salvation.

Unfortunately, this very fact makes Shenmue III a hard sell to newcomers. To those that have never played the first two Shenmue games, or have little interested in the legacy of this series for our beloved pastime, this game will hold almost zero appeal. Several early reviews left little doubt that modern players just weren’t feeling it.

As a recently converted Shenmue fan, however, I enjoyed my time with it in spite of a few frustrations. It was so relaxing to play and I can practically sense Yu Suzuki’s passion within every aspect of the gameplay. They will not get away with this formula for a fourth time though, so Shenmue IV had better try to introduce a few modern, open-world mechanics to bring it up to speed. For now, I can allow one last homage to the past I think.

![]()

- Pure fan service

- Variety of mini-games

- Tranquil tone

- Looks good for AA game

![]()

-

- Needs more fast travel

- Some boring grinding

- English localization sucks

- Dull side-missions

PC Specs: Windows 10 64-bit computer using Nvidia GTX 1070, i5 4690K CPU, 16GB RAM – Played using an XBox One controller

Pieter hails all the way from the tip of southern Africa and suffers from serious PC technophilia. Therapists say it is incurable. Now he has to remind himself constantly that gaming doesn’t count as a religion even if DRM is the devil. Thankfully, writing reviews sometimes helps with the worst symptoms.